Didactic potential of video resources in teaching English to law students

Abstract

Teaching foreign languages in higher education with the adoption of a new Federal Standard is focused on the development of communication skills of students in professional and intercultural interaction. At the same time, the requirements to the English language competence of students are generalized. Nevertheless, it is necessary to create professionally oriented educational materials, to model the pedagogical process, search methods and techniques, technologies, activities to achieve this goal. The use of professionally oriented foreign language video resources has become in demand during the pandemic, when all higher educational institutions switched to the online form of education. The purpose of this study is to check the effectiveness of using a didactic pack of video materials and video-based activities to law students in the “English in Law” course. The hypothesis of this research is to prove the following idea: video materials and video-based activities allow students to become aware of the language of law features and law realia of the English-speaking countries. The research methods used for this study were: quantitative research (a survey, testing, experiment) and qualitative (observations literature review, content analysis). The author includes fragments of legal films and TV series, videos from video hosting sites and platforms for online learning. The researcher defines the methodological subject, language and technical parameters for the selection of professionally oriented video resources. The video resources, selected by the author, contain the targeted language material, standard professional communication tasks, and help law students to highlight the features characteristic of the English-speaking legal culture. The developed methodological support contributes to the expansion of the socio-cultural awareness of students, allows them to incorporate the learned material in communicative situations, thereby preparing law students for professional communication with foreign colleagues.

Keywords: English in Law context, video resources, teaching materials, law students, ESP classroom, intercultural competence

Introduction. Rapid advances in technology and new professions, and increasing numbers of students at all levels have brought many innovations to the educational landscape. A significantly fast access to the Internet-based communications has multiplied the application of videos as instructional tools. Researches on instructional television have started since 1950s, and have emphasized the question of how teaching English can be improved through the use of television (Silver, 1968; Svobodny, 1969). Recent years have shown an explosion of interest in using various video resources for foreign language teaching for academic and specific purposes in this country and abroad (Abdinazarov, 2019, Alhaj, Albahiri, 2020, Badalova, 2019, Codreanu, 2014, Dementyeva, 2016, Feak, Reinhart, 2002, Кuzmina, Popova, 2019, Lobanova, 2015, Muchtar, Laundung et al., 2015). Due to new federal state educational standards the main goal of teaching English to law students at university is to develop the communication skills of students in the field of professional interaction. Current research demonstrates that this competence can be effectively developed within English for Specific Purposes (ESP) courses. Although this requirement is quite generalized, teachers of English (ESP teachers) have to take into account the considerations of course design (i.e. needs analysis identification, specialist discourse investigation, and the curriculum determination) in their work (Basturkmen, 2010) and adapt it to students who are known as digital generation. This constitutes the first challenge as the necessity to design ESP courses by themselves.

Almost all the works devoted to the images of law on television can be described as comprehensive law-related catalogues which can work from an educational perspective (Chase, 2002, Dąbrowski, 2016, Meyer, Davis, 2018). It is important to note that there are studies that describe teaching English to law students (non-native speakers) through video resources (Burmistrova, Stupnikova, 2017, Dąbrowski, 2010, Rotar, Pershina, 2017, Vyushkina, 2016 & 2020, and etc.). Despite of the fact, that there are manuals used at ESP classroom which promote cultural and legal values of English speaking countries (e.g. ‘American Values Through Film: Lesson Plans for Teaching English and American Studies’, 2006; ‘Legal English through Movies’ by Vyushkina, 2000-2015); ‘Lawyering: Moral and Ethical Issues’ by Zykina, 2016, not all ESP teachers share their worksheets and manuals on the topics ‘Law / lawyers in films’, ‘Law / lawyers in videos’, ‘How to work on legal thrillers’). Some of them could have been active writers “for the drawer” for many years, but have not publish a single book. This determines the second challenge as lack of teaching resources.

Thirdly, there is a constant need to update content and technology (activities) concerning the obsolescence of both features. Therefore, it becomes increasingly relevant to design a didactic pack of videos and teaching materials for law students studying English.

Main Part. Objectives. The main objective of the research is to check the effectiveness of using a didactic pack of videos and video-based materials to law students at ESP classroom. It intends to see if there is any influence of using specially chosen videos and video-based tasks on vocabulary acquisition and cultural awareness in ESP. The question which this study aims to answer is the following:

Do video resources and video-based materials have a significant effect on vocabulary acquisition and cultural awareness in law of ESP learners?

The hypothesis of this research is to prove the idea:

‘Video materials and video-based activities allow students to become aware of legal language features and legal realia of English-speaking countries.

The objective and the hypothesis of our research led to the formulation of the following tasks:

- to examine the studies on teaching ESP to students through video;

- to highlight the criteria for the selection of videos suitable for law students;

- to range video resources appropriate to teach ESP to law students;

- to present the technology of developing cultural awareness in law and listening comprehension skills of ESP students.

Literature review. Approaches to teaching English to students through video resources. There are several approaches in research related to teaching English to undergraduate students through video resources. Alhaj A.A.M., Albahiri M/H. have made a detailed outline of Saudi Arabi scientific works devoted to the impact of videos on language learning. Researchers agree that the understanding of grammatical structures can be improved as well as speaking and listening abilities of the learners (Alhaj, Albahiri, 2020). The same aspect of language has been examined by teachers from Karshi Engineering-Economic Institute. Abdinazarov Kh.S, Badalova L.Kh produced a theoretical review of advantages of using video to train grammar skills. Besides picture and sound, this tool also “offers facilities, which are play controls, transcripts, subtitles and captions” (Abdinazarov, 2019; Badalova, 2019). Yan Ding has revealed the most favorable features of an instructional video used in online English courses and shown the students` feedback (Yan, 2018). Tokiko Hori has provided practical examples of the MOOCs application in and out of the foreign language classroom (Hori, 2018). Florina Codreanu has presented a profound outline of different opinions, ideas, and approaches on teaching-learning technical English via sci-fi and tech-movies (Codreanu, 2015).

Philip N. Meyer, Catlin A. Davis have considered that many of the topics covered in the standard first-year criminal law course might have been taught through movies, highlighting the intricate interaction of law and reality and introducing students to the art of legal storytelling. They have insisted that video clips or classical legal movies are not intended to replace the course's regular doctrinal content, but rather to supplement the cases. The movie-based exercises can bring the lectures to life (Meyer & Davis, 2018). Andrzej Dąbrowski has incorporated courtroom dramas in Legal English lessons to contextualize language challenges and introduce students to various legal genres (Dąbrowski, 2010, 2016). Christine Feak and Susan Reinhart have conducted professional programs for nonnative speakers of English who have a desire to become a lawyer in the USA (Feak and Reinhart, 2002). Their course, however, has included an extracurricular component as a weekly series of feature-length films on law-related topics and field trips to a state prison; and a half-day visit to U.S. federal court which may be substituted on watching documentaries on various legal topics at current time.

To strengthen the rationale, a few other pedagogical researches could be added. Russian university professors and researchers have also studied the topic of using video resources at ESP classroom.

Vyushkina E.G. has developed instructional materials to be utilized in an ESP classroom with legal movies to improve law students' professional communication ability. A key idea of the study is selecting film episodes based on a specific communicative situation (“lawyer – client communication; court in session; opening statements; closing statements; lawyer – judge communication; lawyer – lawyer communication; examination / cross-examination, etc.) and collecting such episodes from various films under a certain criteria (Vyushkina, 2016).

Dementieva T.M. has used authentic online video films on different human rights topics; Burmistrova K.A. & Stupnikova L.V. have paid a close attention to the US legal series as a considerable source of professional vocabulary for development of the intercultural awareness of law students; Zaharova M.V. has been focused her survey on forming students’ listening skills in English through video podcasts BBC Interviews Extra; Kuzmina A.V. & Popova N.V. have preferred videos in General English, and documentaries on up-to-date technical matters (Dementieva, 2016, Burmistrova & Stupnikova, 2017, Zaharova, 2018, Kuzmina & Popova, 2019).

Conceptual framework of the course ‘English in Legal Context’. The course of English in Legal Context taught at the department of foreign languages for Specific Purposes is content-based and its syllabus is organized by branches of law and corresponds to the subjects of legal disciplines: (a) Introduction to legal profession, (b) Sources of law, legal systems, (c) the US Constitution, (d) Criminal law. While studying the following topics in Russian, we present relevant topics in English in delay or in parallel, introducing students to certain features of American law and the distinctive linguistic phenomena of the English legal language (Ageeva & Lapekina, 2021). Teachers use the course book “English in Legal Context” (Ageeva, 2017). The course is partly presented online[1] and designed with five foci in mind, all of which are inherently linked.

First, it is important to integrate linguistic abilities with legal material. English in Legal Context is a language course rather than a lecture on a specific area of law. As a result, these classes should blend language competency with particular purpose content knowledge (subject-specific knowledge in our instance), rather than focusing on legal knowledge. Our course prepares students to listen/watch law lectures in English, but it is not a Legal English course.

Second, it is necessary to focus on the development of important aspects of communicative competence in English for Specific Purpose. This means that legal context should be concerned when considering sociolinguistic, discourse, intercultural, and translation abilities.

Third, much attention should be paid to professional terminology. A teacher of English (an LSP teacher) should employ various techniques aimed at consolidating this specialized (legal) vocabulary.

Fourth, the course includes authentic and teaching materials such as real and abridged cases and court decisions which expand the vocabulary of legal terms and expressions, and promote the development of analytical and critical thinking.

Fifth, we incorporate fragments of movies and videos from online educational platforms and motion films or series which help to develop listening skills, and motivate students to be an integral part of international community. When working with such resources, a copyright issue must be considered. In Russia this issue is regulated by Article 1275 which admits the free use of television programs, sound and video recordings for educational purposes by educational organizations.

Requirements to video resources. Based on previous studies and the literature, the researcher has proposed a preliminary list of video resources appropriate to teach English for Specific Purposes to law students:

- video materials on educational platforms such as Research Channel, Teacher Tube, TED, videolectures.net, and the specific YouTubeEDU (Oddone, 2011);

- videos on Massive Open Online Courses (Coursera, FutureLearn, EdX, Khan Academy, Udemy, Study.com, etc.) (Hori, 2018); open university courses (Harvard, Yale, etc.);

- trailers and excerpts from legal movies (Burmistrova, Stupnikova, (2017, Meyer, Davis, 2018, Vyushkina, 2016);

- video podcasts (BBC Interviews Extra, ELLLO); video law podcasts; law podcasts;

- documentaries or specialized movies made by law centers;

- TV courtroom shows (Dąbrowski, 2010).

Certain criteria should be selected to increase the efficacy of teaching English to law students through video resources. The researcher analyzed studies of foreign and Russian authors, teachers of English, blogs and recommendations of visuals for instructors on social learning environments and structured the requirements to video resources which may provide the students` engagement and may be demonstrated in ESP classroom. It should be noted that we consider authentic materials are produced by native speakers or in the countries where English is one of the official languages.

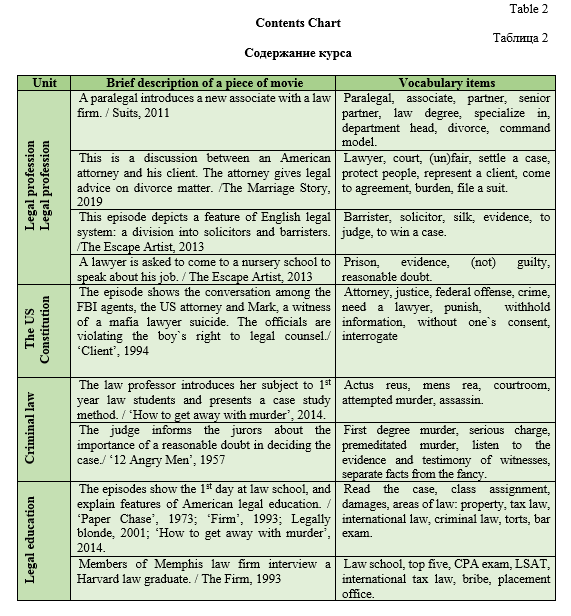

The selection of video resources. The choice of movies for the course was determined by the course syllabus. The ABA Journal`s greatest legal movies (Brust, 2008), articles of law professors and teachers of Legal English in Russia and abroad, current legal thrillers were examined and included into a movie list to use in the course. The table below (table 2) presents topics, a short description of the video fragments presented to the students and sets of legal vocabulary items occurred there.

Full-length movies (Appendix 1) were watched and classified according to the topic and legal terminology. Communicative situation did not play a key role in the classification, though a communicative content and cultural realia were important. After that the selected tracks were extracted by multimedia file converter software, which allowed picking a necessary track, adding or removing subtitles. A text format subtitle file could be easily found in the Internet. The average length of video tracks is between two four minutes. All selected video passages respond to the guidance and recommendations.

The researcher has definitely considered videos on YouTube platform as a brilliant channel of free and fast way of getting a quality source of information. The requirements for these videos have been the same (table 1).

Another type of video resources used in the course was Massive Open Online Course. These courses were recommended for students with B1/B2 level of English as they demanded good listening and language skills. Free online courses known as MOOC provide legal areas and spread for free; they offer mostly pre-recorded webinars and can be completed by students at home.

It is a well-known fact that young people nowadays belong to digital generation who are brought up in a rich information society; they communicate through various types of social networking: VK, TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, etc; consume and produce their own video resources. The researcher inferred that watching videos could be a routine activity; it might relieve the tension of students while completing the tasks.

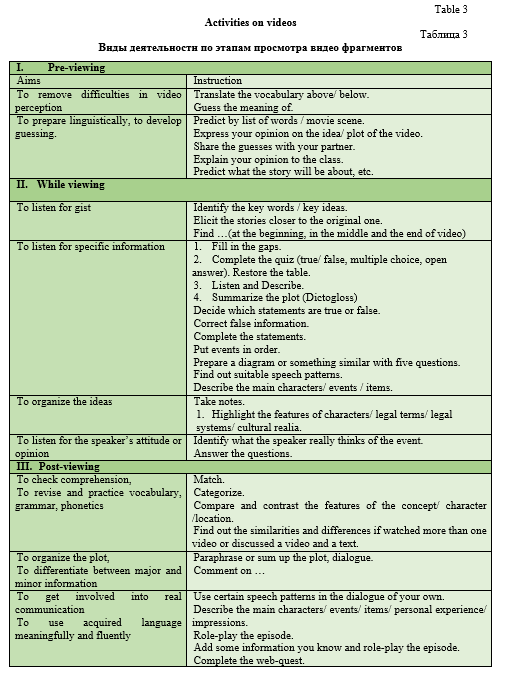

Description of video-based activities. While having selected the materials the researcher has come across many informative and professionally oriented videos, however, has not included them into the teaching pack because they consist of too complicated vocabulary, slang; fluency / intelligibility of speech is insufficiently comprehensible. So there are four units in the teaching pack accompanied by video content. Each unit has a similar composition, though activities and instructions may vary

(table 3):

Methodology and methods. Research design. The researcher conducted the experiment during two years. The research work was divided into three periods: preparation period, experimental period, and post-experimental study. The research tools used for this study were: quantitative research (a survey, testing, experiment) and qualitative (observations literature review, content analysis). Many educational research methods are descriptive; they set out to describe and to interpret what it is.

Participants. The research group was composed of 60 full-time university students attending English classes during their second and third semesters of the 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 academic years. The study was conducted on first- and second-year undergraduate law students with A2 levels of English. These students were divided into two groups of participants with the same level of proficiency: an experimental group and a control group. Each group involved thirty participants. Pre- and post-tests were administrated at the beginning and end of the experiment, and then the data was analyzed.

Materials. The researcher used the following materials in the experiment. She taught English to experimental and control groups of law students using the course book ‘English in Legal Context’ and a set of videos (table 2). The variable condition was that the experimental group received video-based activities (table 3). The control group completed ‘present your findings in class’ task. Pre- and post-tests of video listening comprehension directed to both groups of students.

Data collection. The preparation period was devoted to identify the basis of the research, perform a survey on teachers and students of both groups; select the videos and design the video-based activities. The researcher did two types of surveys to know about the opportunities of ESP teachers to use videos and video-based activities in classroom.

Firstly, ten teachers of the department of foreign languages for Specific Purposes were interviewed to know what video resources they preferred in ESP classroom, how often they used them, and what feedback they got.

The difference in the proficiency level of students was also important. The participants should be of the same level of English. The research used testing to check the level of proficiency of the students who entered law faculty. That pre-test included sections: language and culture, and video listening.

Besides testing the researcher conducted a survey to know the opinion of students on video resources in learning English.

During the experimental period which was implemented for two terms the researcher taught both groups of students.

After the collection the major data from the pre-test, the tasks and activities were implemented using a set of selected video resources and video-based materials for the experimental group. The teaching process of experimental group trough videos suited the overall curriculum framework.

Step 1. Pre-viewing. This step prepared students to comprehend a video material through warm-up activities intended to ask & answer the questions related to the topic, brainstorm relevant vocabulary, and predict the plot of the video.

Step 2. While viewing. First, the teacher played the video fragment for gist – to help learners to get the general idea of the story. The pause button could be used, if necessary, to focus on sections students had difficulty in understanding. Next time the video could be played mute or with sound and the ‘inferring the culture’ exercise was done to produce the cultural realia of the video. Students might figure out what was being said, who was speaking, and what was going on by using contextual cues and their understanding of the topic.

Step 3. Post-viewing. In this step, the teacher asked either to retell the episode (e.g. the ‘snowball’ technique) or comment on or paraphrase the situation. It was time to check predictions and choose the most accurate listener. In addition, students could be asked to characterize and compare the items (characters, realia, and events) or alternatively, students were asked to complete exercises after they had watched a segment. Finally, s speaking technique as role-play was welcome. More detailed procedure can be seen at table 3. A lesson plan description based on the topic ‘Law school’ is presented in Appendix 2.

The final task for each unit for both groups was a post-test, a kind of an achievement test measuring students' ability to repeat language and legal culture elements that they have learned and mastered at some level.

Research Results and Discussion. According to the survey, 50% of the teachers used instructional video clips on the Youtube platform once a week inside and outside the classroom. 30% of the respondents use video clips of online courses from time to time. The most popular activity reported by teachers was to watch the video and present findings in class. Frequently, teachers do not attempt to select appropriate assignments for their students because this kind of activity takes much time to find a certain video and develop the video-based tasks. Most teachers wish they had more knowledge in law, better IT skills, and time to design teaching materials.

In regard to full-length movie classification (Sherman, 2003), 20% of the teachers used the illustrated talk (a teacher gives a commentary to culture-specific items while watching the movie, stops at the climax, offers the students to make guesses about the end of the story, and do suitable recap activities at home), 40 % of staffers incorporated the salami tactics (a movie is divided into several episodes and watched during several lessons following a common approach – pre-viewing, while viewing, post-viewing exercises), the independent film study (watching a movie at home and being prepared for a class discussion) was spread among 70 % of respondents, though this possibility was offered to the students with strong level of English. One fifth of the teachers used all types of guided watching.

Thus, the survey could sum up that all teachers used video resources in their work, the majority of staffers incorporated Youtube videos, full-length movies or the salami tactics in the classroom. The interviews depicted that using videos in the classroom is often a challenge. English class, which involves watching an episode of any legal topic, takes teachers` proficiency both in English and some awareness in law, creativity, stamina and much time. Sometimes they lack legal knowledge and tend to consult law teachers or experts.

The next important step was to analyze the data about the students. It appears that both groups of applicants showed satisfactory or good results on language. However, listening skills and cultural awareness, depending on the proficiency of English and English-speaking culture view, were rather ordinary. Listening tasks were hard to be completed by those who had not taken the Uniform State Exam in English, an international English-language proficiency test or had not spoken with a native speaker. The students with B1 level of English did not have any difficulties in listening comprehension on general English topics. Students with A1/A2 levels of English found the listening tasks complex. Some students expressed a negative reaction on listening exercises; they were ready to complete language tasks, but listening comprehension activities made them feel frustrated.

The survey showed that the majority of students hardly ever used the variety of video resources spread in the Internet to improve their English. During the Covid-19 period they had to watch educational lectures in Russian and be online. Students with B1 level of English watched films and video clips in English from time to time.

In order to form the experiment groups of participants and find out if there were any significant differences between the pre-test scores of the students in the experimental group and the control group, the researcher carried the Mann Whitney U Test. This test was performed to determine that the samples in both the experimental group and the control group were similar in their proficiency level of English and their ability to recognize and comprehend the targeted vocabulary. A significant difference in the result would suggest that the study was unconvincing. Table 4 gives the results.

The study of the findings in Table 4 reveals the results of Mann Whitney U test for the pretest academic achievement scores of the students in the experimental and control groups did not show any statistical difference (Z=0.036; p=.48>.05). The rank average of the pretest scores of the experimental group students was 30.6, while the students in the control group had a pretest score rank average of 30.4.

A variety of watching solutions depends on students` language proficiency. For example, such routine listening tasks as ‘tick the words you hear’, ‘underline the words you do not hear’, ‘tick a true answer’ received more right answers, than cloze tasks (‘fill in the gaps’, ‘complete the statements’) which tend to be more difficult. These tasks as ‘answer the questions’, ‘decide if the following statements are true, false or doesn`t say’ demand a better command of English of the learners and got less true or incomplete answers.

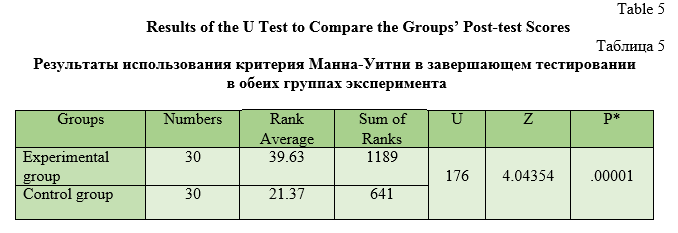

The pre-tests and post-tests were not the same. The scores were collected and compared statistically using Mann Whitney U Test in order to see if there was any significant difference between the pre – and post-tests in each of the two groups of learners to state their progression level after using a set of video materials and video-based activities.

The examination of the findings in Table 5 demonstrates that the results of the Mann Whitney U test concerned to the post-test academic achievement scores of the students in the experimental and control groups revealed a statistically significant difference at the level of p<.05 (Z=4.043; p=.00001<.05). The rank average of the post-test scores of the experimental group students was 39.63, while the students in the control group had a post-test score rank average of 21.37.

The analyses had shown no significant difference between the rank averages of the groups’ pretest academic achievement scores; however, an examination of the rank averages of their post-test academic achievement scores demonstrates that the students in the experimental group had higher academic achievement than those in the control group. This result indicates that the experimental group students attained higher success after the experimental application when compared to their peers in the control group. Based on the findings, it is possible to conclude that incorporation of videos and video-guided materials significantly increased the academic achievement levels of the experimental group of students.

Conclusion. This study verified that using a didactic pack of selected videos and specially designed video-based activities improved law students’ English listening comprehension skills, language acquisition, and cultural awareness of legal concepts. Furthermore, the researcher proved through the experiment that the usage of the didactic pack led to mastering professional vocabulary and getting a faster response in listening tasks. The findings of the study suggest that teachers should be encouraged to use video resources and video-based activities to law students in their classrooms. It is necessary to select videos according to the certain criteria list in order to achieve higher scores in language acquisition and cultural awareness. Video-based activities have demonstrated better results comparing to ‘present your findings in class’ task. The current study should be taken as a foundation for other studies performed in ESP classrooms for further development of video-based activities and progress test validation.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

- to teach legal vocabulary related to ‘Legal education’ topic.

- to develop language, subject-specific and intercultural competences.

- Skills practiced: listening, writing, and speaking.

- Heather Pickerell is a first-year law student.

- She has been at Harvard Law School (HLS) for a week.

- She is nervous of a large size of the group, people of various backgrounds, race, and gender.

- Before law school she dealt with civil matters.

- During their first year, law students divided into small sections of 20; everyone takes required classes as torts, civil procedure, property, etc.

- Heather pays much attention to her study group.

- There`s also much to do outside of class in campus.

- Law school applicants should be well-prepared for LSAT to enter law school.

- She agrees with the opinion that law students of HLS are too competitive.

- What working experience does she have?

- What does “to be cold-called” mean?

- What outside activities does she have?

- Can all law students apply to summer internships?

- What movies about lawyers does she mention?

- What advice does she give to those who want to enter law school?

- What is an application process to HLS?

- Look through the reasons of a challenging study at law school. (You have done it on the text “How to become a lawyer in the US” at the beginning of the class). Tick the things you have come across in the video. Add some features not mentioned there. What things are odd?

- Make up/ look through the specific features of legal education in the USA. What features did you know before? What items are new for you? Make up a list of 10 reasons what makes study at HLS so prestigious?

- Divide into four groups. The goals are given below. Give some examples. This may demand some time preparation. (ten-twenty minutes)

- Make up a list of advantages / disadvantages of studying law at HLS.

- Make up a list of advantages / disadvantages of studying law at law faculty in Russia.

[1] English for Professional Purposes, URL: https://sites.google.com/site/eflforpp/english-for-law -students/legal-education-in-the-us-1 (Accessed 12 May 2021)

[2] How to make a great tutorial video, URL: https://blog.udemy.com/how-to-make-a-great-tutorial-video/ (Accessed 26 June 2021).

[3]Video recording recommendations, URL: https://support.stepik.org/hc/en-us/articles/360000173194-Video-recording-recommendations (Accessed 26 June 2021).

[4] A Day in the Life: Harvard Law School Student, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Q-mCNJp8X0 (Accessed 26 April 2021).

Reference lists

7-23.