Highlights:

- Experiences of EFL students of their reading difficulties and strategies are explored (Participatory);

- Autodidacticism of reading strategies showed cognitive reading strategies as the most used ones, followed by metacognitive and socio-affective – and insufficient vocabulary during autodidacticism seems to be the number one reading difficulty (Action); and

- EFL students share reading strategies and difficulties to increase their awareness and other EFL students (Research).

Introduction. Learning strategies has been regarded as an essential field of education, and several EFL students face reading difficulties and problems when reading texts, while too many previous studies were mainly focused on students read in class that depends on different reading states rather than reading on their own. Moreover, a few previous research pieces were concentrated on reading passages in general rather than challenging texts.

Over the last few decades, there are plenty of studies all over the world that have investigated various use of reading strategies of EFL students and difficulties they face when they are reading texts based on three reading stages in the classroom (Young & Oxford, 1977; Paris et al., 1991; Brantmeier, 2002). However, most previous studies have primarily concentrated on different reading strategies based on the reading stage during the class rather than reading independently.

Additionally, although there are a few previous types of research were focused on reading issues or difficulties they encounter when ESL/EFL students read texts, it is necessary to explore the difference between the two different types of reading; it also seems that this kind of study has not received sufficient attention in the EFL context of Glasgow. Thus, this research focused on challenging texts, which specify the range of all the reading texts.

Reading is a complicated cognitive activity that is important for appropriate functioning and for acquiring information to require meaning construction and memory integration in current society (Zare, 2013: 1566). There are different definitions of reading strategies based on previous studies. Reading strategies has been defined as a mental process that readers choose to adopt to accomplish reading tasks consciously and successfully (Zare, 2013: 1567). IKEDA et al. (2003: 49) state that language learning strategies are a significant factor in successful language learning. Reading strategies are also techniques and approaches that the readers use to make their reading more effective (Zare, 2013).

According to Oxford (2011), the purpose of ESL/EFL learning strategies is to enhance their achievement or proficiency of the language, finish a task, or make learning more successful, efficient, and straightforward. Based on previous studies, there are two categories of reading strategies. Reading strategies were divided into four types: problem-solving strategies, global strategies, support strategies and socio-affective strategies (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002: 121; Huang et al., 2009).

Another classification of reading strategies is cognitive reading strategies, metacognitive reading strategies and socio-affective reading strategies. According to several previous studies, the latter categories are used more frequently (Oxford, 1990; Chamot & O'Mally, 1994; Brown, 2007; Williams & Burden, 1997; Cromley, 2002; Huang et al., 2009: 24). Thus, this study focused on the three principal strategies: cognitive, metacognitive, and social and affective.

To start with the cognitive strategies, Brown (2007: 134-135) demonstrated that cognitive reading strategies refer to using the written materials by learners in a conscious way to boost their learning, for instance, insert vocabulary in a meaningful context or use the information available to make guesses about new items meaning or fill the gap in a message. Chamotand O'Malley (1994) also indicated that cognitive strategies are adopted to complete a particular cognitive task when reading texts. According to Williams and Burden (1997), cognitive strategies are defined as mental processes directly concerned with information processing to learn, obtain, check, or use the information. Brown (1994: 115) claimed that cognitive strategies are more restrained to particular learning tasks and comprise more direct study material operations.

In general, studies in both L1 and L2 reading research provide a binary division of cognitive strategies as bottom-up and top-down. Cognitive reading strategies involve various strategies the learners may use that can facilitate language learners read more effectively and quickly (AL-Sohbani, 2013): translation, grouping, note-taking, deduction, recombination, imagery, keyword, contextualisation, elaboration, repetition, prediction, transfer, inferencing, and so on (Brown, 2007). There are different descriptions for each different strategy. For example, note-taking can be described as writing the key points down, main idea, summary, or outline of information in speaking or written (Brown, 2007: 135).

The second reading strategy is metacognitive strategies, which are the functioning of monitoring or processing cognitive strategies. Different definitions of metacognitive strategies are defined by diverse scholars (Shamsini & Mousavi, 2014: 41). Brown (2007: 134) stated that the term “metacognitive strategies” include monitoring their output and comprehension or self-evaluation for learning after completing a task. Cromley (2002) indicated that metacognition is that learners are employing themselves in metacognition, for example, thinking about whether they are tactful or checking their production or deciding whether the task can be completed and so on. According to Şen (2009: 2301), metacognitive strategies involve the awareness of their thinking about their learning process. There are several different metacognitive reading strategies: advance organisers, directed attention, self-talk, self-management, operational planning, self-monitoring, delayed production and self-evaluation (Brown, 2007: 134). For instance, operational planning is described as “planning for and rehearsing linguistic components necessary to carry out an 'upcoming' language task” (Brown, 2007: 134). Quite a few previous studies claimed a critical relationship between the use of metacognitive strategies and reading comprehension. It is essential to use metacognitive reading strategies if the readers want to get a successful understanding of reading and effective readers are good at adopting metacognitive strategies (Cromley, 2002; Şen, 2009; Shamsini & Mousavi, 2014; Huang et al., 2009; Anderson, 1991; Block, 1986).

Strategies in the socio-affective category comprise social strategies and affective strategies that refer to learning and interacting with others for understanding culture like asking for clarification, and cooperation while affective strategies involve managing feelings and emotions such as dealing with stress and fear appropriately on their own, self-talk, or using music when they are doing reading tasks and so on (Brown, 2007; Huang et al., 2009: 24). For instance, cooperation refers to gaining feedback or comments, simulating a language activity, or pooling information by discussing with one or more peers by emails or in chat rooms. Questions for clarification involve asking for repetition, paraphrasing, elaboration via teachers, professors, or native speakers to understand betterthe reading task (Brown, 2007, Huang et al., 2009).

Regarding the above three main strategies, eleven different reading strategies based on cognitive, metacognitive and socio-affective reading strategies were included in this research: note-taking, imagery, inferencing, translation, highlight/keyword, operational planning, self-evaluation, self-talk and cooperation in the current study. Furthermore, these differentreading strategies were involved in the questionnaire and semi-structured interview to test what reading strategies EFL students use and their difficulties when reading challenging texts on their own in an international college in Glasgow.

The primary significance of this studies lies in that lots of previous studies are mainly concentrate on ESL/EFL students read texts in the classrooms with teachers' guidance. The use of reading strategies thus depends on three different reading strategies in the class. In contrast with supported reading on their own, there are three reading stages in the classroom: pre-reading stage, while-reading stage and post-reading stage. EFL students use different reading strategies in various phases (Young & Oxford, 1977; Paris et al., 1991).

The purpose of this research was to investigate EFL students' perceptions of reading strategies they use when reading challenging texts on their own and finding out if the students face problems, and what issues or difficulties when they read challenging texts on their own to prepare for studying in English at Glasgow University. Thus, this current study answered the two research questions below.

What reading strategies do EFL students use when reading challenging texts on their own when preparing to study in English?

What difficulties do EFL students encounter when they read challenging texts on their own when preparing to study English?

Methodology and methods. According to Onwuegbuzle and Leech (2006: 475), research questions are essential in quantitative and qualitative research since research questions will narrow the study and research objective via particular questions. To examine EFL students' perceptions of reading strategies and difficulties they encounter when reading challenging reading passages in English by themselves rather than in Glasgow's classes, this study adopted the qualitative approach to investigate more details deeply. Saunders et al. (2012: 161) indicated that ‘qualitative’ is often used as a synonym for any data collection technique such as interviews or data analysis procedure such as categorising data that generates or uses non-numerical data.” Cohen et al. (2007) claimed that it is beneficial to quickly generalise quantitative data by questionnaire, especially for a large sample size; there are no geography restrictions.

This study used a self-completed paper questionnaire through face to face was designed and used to gather quantitative data, but they analysed it in an interpretive way. That means the research delivered the questionnaires and waited for respondents to finish the questionnaire to collect data faster (Saunders et al., 2012, p. 420). Therefore, the self-completed questionnaire was selected because it was a quick and easy way to give out the questionnaire after participants' permission was suitable for collecting data. Participants might ignore filling the questions if they used email or mail questionnaires.

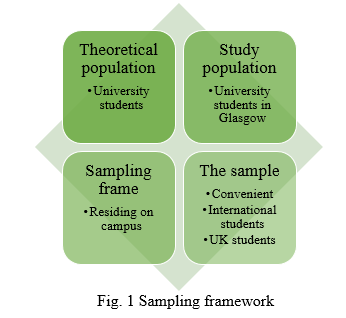

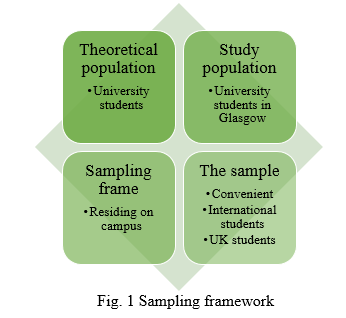

Sample. Due to resource and time constraints, the sampling strategy selected a non-probability sampling that was more suitable and effective for this current study. It is impossible to access the whole population of all the EFL students if adopting the probability sampling strategy. Non-probability sampling means “selection of sampling techniques in which the chance or probability of each case being selected is not known” (Saunders et al., 2012: 676). Considering convenience, the non-probability sampling technique was implemented in this research since it is hard to examine all the reading strategies and reading difficulties.

Consequently, this study randomly selected participants in the standard room of the institution in Glasgow. 15 EFL students who study pre-master currently in this institution which belongs to the University of Glasgow to enter the University of Glasgow to learn were selected to investigate EFL students perceptions of difficulties and strategies they use to read challenging texts on their own when preparing to study in English at the University of Glasgow. Their ages were all over 18 years old, and the proficiency level was assigned as upper-intermediate since they are preparing to study at Glasgow University after they finish their pre-master courses. I chose this site's participants because the students in this college are all international students who regard English as a foreign language and are taught English language courses that involve reading skills.

Therefore, choosing these 15 international students could have various nationalities such as Chinese, Japanese, Arab, and Russian, which may impact reading strategies and reading difficulties when they read a challenging reading text than other studies. Furthermore, many previous findings and results were outdated; it is crucial to explore the current strategies and difficulties when reading EFL students.

Moreover, this research did not classify students by variables like gender, age, nationality, first of all, because it tended to find the reading strategies and difficulties by students themselves in general, and the primary purpose was to investigate how different when students read a challenging text rather than in classes. Secondly, the sample population is not large enough for these variables to be considered, as they would probably have no striving significance and effects.

Measures. There are 23 closed questions: all frequency Likert scale questions from never to always for testing different reading strategies and reading difficulties or problems based on the relevant points identified in the literature review section. Take a question as an example here: “I write down the main idea important points when I read a challenging text”, “I feel worried when I encounter vocabulary I do not know.” According to Saunders et al. (2012: 482), closed questions are simpler and faster to gather information from different respondents, and the answers are simple to code and statistically analyse with fewer errors. In this research, the researcher analysed the trends in the answers based on an interpretive method.

However, some participants refused to fill the questionnaire questions because they had a short break in the standard room not have sufficient time to finish the questionnaire. Therefore, avoiding sensitive time is helpful to gather information successfully. Such as lunchtime, class short break time, or students are hurry to classes. The pilot study was also considered significant in the study; some participants might not answer all questions as they were ambiguous and less confidential.

According to Cohen et al. (2007), it is crucial to consider whether the questions are necessary, clarity to read, providing the correct amount of choices, appropriate information, truthfulness and bias answer or not. It thus checked for accuracy of translation and pilot tested by fellow students or tutors. For example, the challenging text could confuse participants because they may not know what kind of text can be difficult. Consequently, a supervisor and two classmates at the University of Glasgow piloted and detected these questions. After piloting, the researcher will show them an IELTS text before they complete the questionnaires and interviews.

Also, there were no open questions at the bottom of the questionnaire because this study conducted the semi-structured interview, including available questions as the second instrument to explore more in-depth. A semi-structured interview refers to several questions that focus on the specific area and are designed to elicit similar responses from participants. However, it follows a pre-prepared plan that could vary the sequence in which questions are asked and ask new questions through one to one (face-to-face) based on the different situation in the context of the research (Saunders et al., 2012: 681).

In this study, qualitative data were gathered by a semi-structured interview (in-depth interviews). It is suitable for collecting qualitative data to conduct more about participants' perceptions and feelings to develop the research. A draft of the interview questions was designed in advance, and some questions were altered that depends on the response, facial expression and behaviours from interviewees. The interviews were conducted in a specialised interview room at the Fraser Building; the researcher has built a good relationship with the two interviewees to make the discussions run smoothly.

This research asked two students who volunteered to interview about their perspectives and feelings of reading strategies and reading difficulties when reading a challenging text through semi-structured interviews. Each interview lasted 15 minutes for each participant. There are 12 questions which include open questions that allowed participants to define and describe a situation or event. Saunders et al. (2012: 391) reported that available questions involve the following question: ‘what’, ‘how’ or ‘why’ that encourage participants to express their attitudes or show development and extensive answers. For example, in this recent interview, ‘How do you feel when you read a challenging text?’ ‘Why do you feel worried sometimes when you face a difficult passage?’

The semi-structured interview was conducted in English entirely because the interviewees are international students who speak different first languages. Easterby-Smith et al. (2008) indicated that bias could be avoided if use open questions. Additionally, probing questions were designed in the semi-structured interviews. Probing questions refer to investigate the answers of respondents that are rather important to the research topic. It was similar to open questions but requested more responses (Saunders et al., 2012: 392). Take Q7 as an example in this interview, ‘Do you think you are an effective reader? Please tell me more about that?’

However, the interviewees who would not answer all the questions might not recognise many theoretical concepts such as cognition, affection because their understanding of the concepts may change (Saunders et al., 2012: 390). Therefore, such terms and tricky words in the questionnaire were avoided. After revising, a tricky question that included the term metacognition was replaced by some easy examples. Moreover, an IELTS reading passage was showed to interviewees before they started to answer the interview questions. This reading material part was presented in the material section further below.

The threat of reliability and validity were taken into account. Reliability is a crucial feature in research quality (Saunders et al., 2012: 192). Some issues occurred during collecting data that impeded data collection progress due to the threats of reliability, which came from both researcher and participants. For instance, in the current research, the researcher asked one student to fill the questionnaire at lunchtime in the standard room in that college in Glasgow; however, the student refused to complete it because it had a class p.m. had no sufficient time to finish. Hence, considering a proper time and suitable and secure location for participants is rather significant (Felder & Spurlin, 2005).

This study was approved by an Education-Ethics officer in the School of Education at Glasgow University before the research. Because the participants are the students who run for foundation and preparation for Master’s degree students, it was essential to send a permission request, consent forms and ethics approval form of questionnaire and interviews for that college’s leader. Besides, the participants agreed to take part in this research before asking for permission. Besides, the participants agreed to participate in this research before attributing the questionnaires and conducting the interviews.

Thus, the consent form was required to sign their names on it. According to Saunders et al. (2012), it is significant to acquire consent forms from the participants. Simultaneously, they were informed to withdraw if they felt uncomfortable or were asked some sensitive questions. Furthermore, all the information gained from the questionnaires and interviews was kept confidential, and participants’ signatures and private data were removed from the outcome. In terms of interviews, recording semi-structured interviews was informed to the interviewees before implementing interviews.

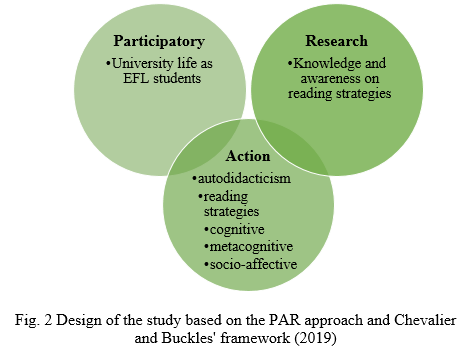

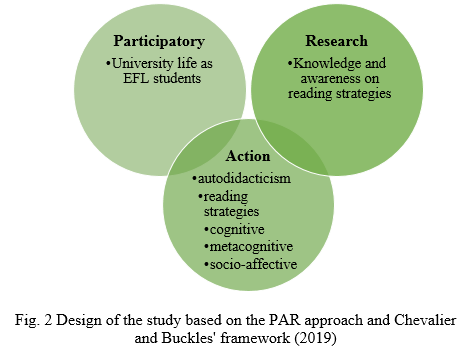

Design. The study design is based on the PAR, mainly Chevalier and Buckles (2019), where the three elements interact together to form change (i.e. participatory, action, research).

Procedures. The paper questionnaires were distributed in Glasgow on July 13 in 2015, and the data also was collected at 1 pm on July 13 face to face. Because the first and third authors studied at Glasgow University, 15 students were chosen randomly in the standard room at an international college in Glasgow. The male and female participants included a few different nationalities based on the researcher observed during the formal room survey. The researcher would show an IELTS reading text as a challenging text about ‘the little ice age’ before allocating the questionnaires. The students were instructed and encouraged to scan through the reading passage to complete it smoothly.

However, they had the right to decide whether to adopt the text as their reading help. Boyle et al. (2003: 282) suggest that if the participants felt comfortable, they had the right to withdraw at any time. Each questionnaire took each participant 5 minutes approximately, and the whole process of collecting data from the questionnaires was last 2 hours. The researcher facilitated and explained to the respondents if they did not understand any vocabulary or had any confusion about the questionnaire during the process. Besides, the data of questionnaires were managed anonymously and confidential by the researcher. Furthermore, consent forms were shown to all the participants who agreed to sign their names on them.

In terms of the two interviews, the principal investigator was conducted on July 15 in 2015, and the qualitative data were collected between July 16 and July 18 through one to one and face to face. The three separate interviews were all implemented at about 3 pm in Glasgow University Library, each of which lasted 15 minutes, which allocated each student an IELTS reading text to know what a challenging text is before interviewing. Instructions were also given to help participants get familiar with the topic. Similarly, the data of interviews would keep interviewees anonymity as well. The audio-recording device recorded the interview responses to transcribe their account, and the interviewer took notes during the interviews. Saunders et al. (2012: 394) claimed that note-taking is beneficial for maintaining the researcher’s concentration to provide a back-up if the audio recorder does not work, suitable for transcription when the researcher analyses the data. After the interview, the interviewees were required to put their signature on the interview consent forms, representing the researcher had already asked their permission.

Once data were collected, the data were analysed qualitatively because the current study is qualitative methodologically. As mentioned above, the data were collected from questionnaires and interviews. First of all, the 23 questions were analysed by coding because each question was a sentence. Codes can help meanings be memorised and recalled quickly and more effortless.

The participants were asked to scan one challenging text of about 500 words each before a 15 minutes interview for each participant. The passage was extracted from an IELTS book eight published in the University of Cambridge ESOL Examinations. I selected the IELTS reading text because all the participants might pass or prepare for the IELTS test. Thus, they had the same English level and ready to study in English at the University of Glasgow. Besides, most of these EFL readers were likely to read in their academic curricula was IELTS since it was more challenging for them in their reading setting. The difficulty levels of the reading passage were set at the upper-intermediate level.

Results. In the present research, two questions were raised. First of all, the use of EFL students' reading strategies when they read challenging texts on their own was investigated, such as note-taking, translation, and self-evaluation. Secondly, EFL students' difficulties when they read complex texts on their own were examined based on the data from questionnaires, especially from interviews, because the data from interviews were detailed and rich – for example, reading anxiety-like tension, desperation and fear, short vocabulary.

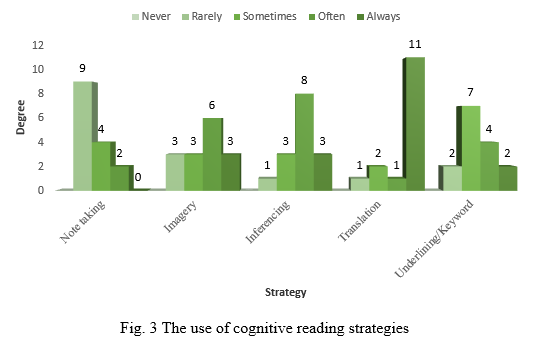

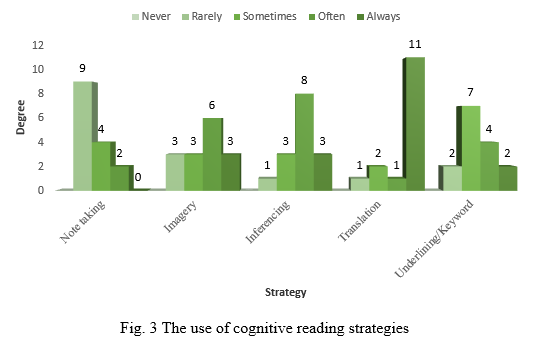

Reading strategies of EFL students. In the questionnaire, there are nineteen frequency Likert scale questions were tested about different reading strategies, which were coded by note-taking (Q1), imagery (Q2~Q4), inferencing (Q5~Q6), translation (Q7~Q8), Highlight/keyword (Q9), Rereading (Q10), Planning (Q11~Q12), Self-evaluation (Q13~Q15) and Cooperation (Q16). There are nine questions (Q1~Q9) that were all counted cognitive reading strategies. More precisely, as shown in Figure 3, very few students used ‘note-taking’ as their strategies when they read a challenging text independently, while most students employed ‘translation’ when they read challenging texts on their own. Similarly, the interviews' result shows that the two interviewees did not take notes very often while reading challenging texts independently. However, interviewee 1 said:

“Sometimes, I take notes if I feel it’s really important, as you know, in the IELTS text, we have questions, I read the questions first, if there are key words in the text, I make notes on the questions and try to find the key words in the text, but I usually underline the key words in the content.”

Furthermore, the interviewees also thought taking notes is helpful while reading a challenging text individually. For example, interviewee `1 expressed, “um, taking notes is useful, because I cannot remember all the reading things, so when I take notes which are the key points, I can think of other things, it makes me more memorising”. Similarly, interviewee 2 stated:

“Very often, no matter in an exam or read at home, I take notes because it’s a good way to get a high mark. And it’s really useful for me; for example, there are not lots of time to read the whole text during the exam. I will have a plan in my mind to find the answers and locate the keywords to help me find the answers quickly through taking notes. But If I just read a newspaper, I never do that”.

Thus, the reading strategy of taking notes was not the most frequent one while reading a challenging text; generally, underlining tends to be used more when they read on their own by students according to the semi-structured interviews. Based on ‘translation’, the female interviewee employed a translation strategy very often. For instance, one of the interviewees said she always translates the whole sentence to get the idea into her language. Another male interviewee did not mention translation at all.

Additionally, many participants were still, but few chose ‘imagery’ as one of three strategies than ‘note-taking’. In terms of ‘inferencing’, most of the respondents selected it as their reading strategy, and only one student rarely used an ‘inferencing’ strategy when they read a challenging text by themselves. The rest of the participants sometimes employed it as their reading strategy. The same finding from the interviews, all 2 participants used a ‘guessing’ strategy rather frequently. For example, the female interviewee mentioned, “I just skip it, translate the whole sentence to get a general idea and ignore that one unknown word and guess from the context sometimes” (interviewee 1). In comparison, interviewee 2 said, “Um, firstly, I may guess what it means. If I cannot guess the meaning, I just skip that and keep reading, I will try to guess it from the available information from the content”.

In terms of ‘highlight/keywords’, it can be found from the questionnaire that less than half of the students often/always adopted a ‘highlight/keywords’ strategy when they read independently. Almost half of the participants employed it as their reading strategy sometimes. Surprisingly, nobody chose ‘Never’ according to these five different strategies of reading. In contrast, the interviews participants preferred highlighting the keywords when they read a challenging text independently. For example, the male interviewee responded that both ‘note-taking’ and ‘highlight/keywords’ were useful. It was an excellent way to get a high mark, especially during an exam. It helped him locate the keywords quickly. Moreover, the ‘summarising’ strategy was never used by the 2 participants according to the interviews. For example, male interviewee 2 said: “Never, I normally understand the text through the reading so that I will not summarise on my own”.

Interviewee 1 answered that she rarely employed the ‘summarising’ strategy; her purpose is to get the correct answer rather than to summarise the idea. In summary, most participants preferred using ‘translation’ and ‘inferencing’ strategies than others when they read challenging texts on their own in Glasgow based on the questionnaires and interviews.

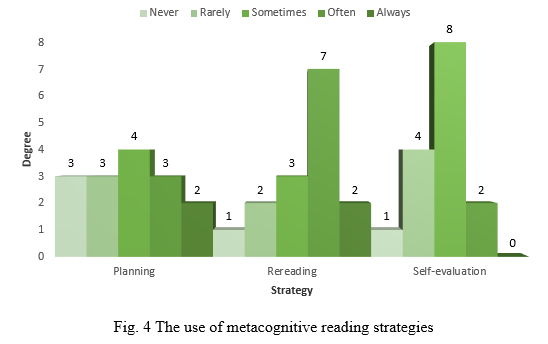

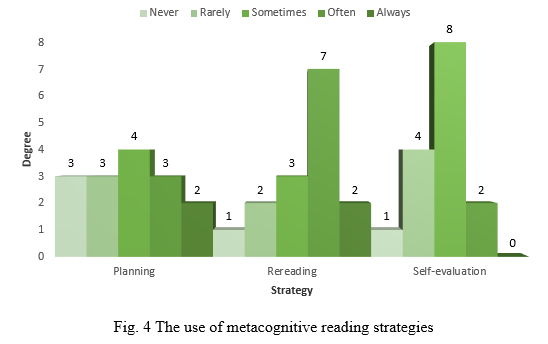

In terms of metacognitive reading strategies, frequency Likert scale questions were designed to investigate the use of ‘planning’, ‘rereading’ and ‘self-evaluation strategies of reading by EFL students in Glasgow. It can be seen in Figure 4, and there was a balanced distribution of use of the planning strategy by participants, which means there were no apparent trends of this strategy. However, based on the interviews, both interviewees had a plan or goal in their head to get the correct answer while reading a challenging text.

For example, the male participant responded that he combined taking notes and operational planning to help him be more focused. He mentioned, “During the exam, there is not much time to read the whole text. I have a plan in my mind to find the answers and locate the keywords by taking notes.” Compared with planning, there was a striking tendency of using the ‘rereading’ strategy, and most participants preferred employing the ‘rereading’ strategy among all students. Similarly, the two interviewees answered that they knew what they should focus on, usually focused on the questions first, and then tried to find the relevant information in the passage, which means they used selective attention while reading a challenging text on their own.

However, many respondents chose ‘sometimes’ of using the ‘self-evaluation strategy, and only a few participants used this self-evaluation strategy frequently when they read a challenging text on their own in Glasgow. According to the finding from the interviews, there was a slight difference from the questionnaire. The students who participated in the interview checked their language and content while reading. In conclusion, the number of participants who preferred using the ‘rereading’ strategy was much more than those who employed planning and self-evaluation strategies.

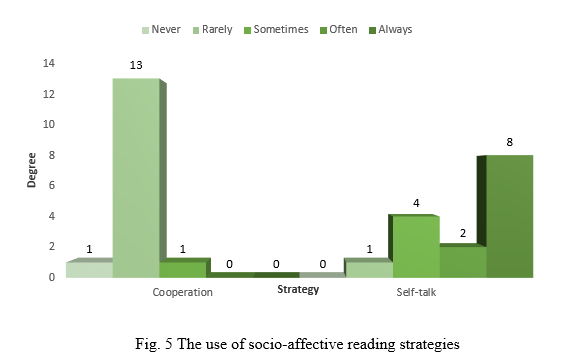

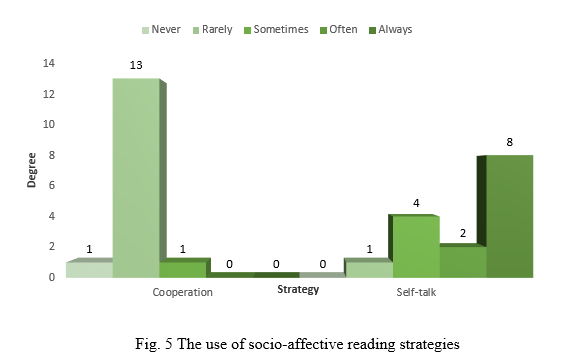

Based on Socio-affective strategies of reading, three questions were asked about the use of ‘cooperation’ and ‘self-talk’ strategies by EFL students. Both the ‘cooperation’ and ‘self-talk’ strategies were witnessed as apparent trends. To be more specific, as can be seen from Figure 5, almost all the participants rarely used the ‘cooperation’ reading strategy when they read a challenging text on their own. In contrast, the great majority of participants always employed the reading strategy of ‘self-talk’. According to the interview transcription, both interviewees did not use the ‘cooperation’ strategy when they read independently.

For example, the male students responded: “Well, I always solve reading problems by myself, even in the class, you know, I am not a kind of outgoing person, I do not like working with peers when I read a challenging text”. Adversely, the interviewees' strategy of ‘self-talk’ was frequently used by the interviewees when they read a challenging text on their own. For instance, the second respondents answered: “Well, I think it is a good way for me to adjust myself, especially during an exam” (interviewee 2). At the same time, the first respondent stated: “Yes, I always talk to myself when I read on my own, especially for a challenging text. Self-talk can remind me thinking in the reading context and help me relieve my tension if the text is too difficult for me as well” (interviewee 1).

To conclude, many more participants adopted the self-talk reading strategy when they read challenging texts based on questionnaires and interviews.

Overall, as shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, it can be seen that the three main reading strategies were all employed by the participants when they read a challenging text on their own in general. More precisely, most EFL students who prepared an English study at Glasgow University used cognitive reading strategies very frequently that were much more than metacognitive reading strategies. Additionally, the participants who employed metacognitive strategies were a bit more than using socio-affective reading strategies by the participants based on both questionnaires and interviews.

Reading difficulties of EFL students. There were five frequency Likert scale questions in the questionnaire, which were asked about EFL students’ perceptions of challenges they use to read challenging texts on their own when preparing to study in English at Glasgow University. Themes coded the five questions: reading anxiety, reading speed, language differences, prior knowledge, vocabulary and English exposure. As shown in Figure 6, many respondents often/always had ‘reading anxiety which affected their reading comprehension.

Similarly, according to the interviews' response, the two interviewees also thought they had serious ‘reading anxiety’, especially reading a challenging text independently in an exam. For example, interviewee1 responded that “I feel like I do not want to read it, and I feel stressed.” Interviewee 2 expressed: “I feel worried that I may not understand the text.” Besides, Slow ‘reading speed’ and ‘language differences’ were another two difficulties for the participants that account for a large number when they read a challenging text based on questionnaires, which is slightly different in the interviews.

The female interviewee thought reading speed was very slow, impacting her reading comprehension, particularly in reading a challenging text, which the field was not familiar with. For instance, interviewee 1 answered: “The field or the content I am not familiar with will make my reading speed rather slow even make me do not want to read it, especially for a specific subject like science, chemistry etc.”

Also, the participants' short vocabulary was the biggest problem when they read a challenging text independently, which was the same finding from the interviews. Both males and females considered short vocabulary as their severe reading difficulty while reading a difficult text independently. For example, the male interviewee responded twice, “Eh, I think maybe the vocabulary because some vocabulary is complicated that I cannot understand”. He also mentioned, “English for me is a foreign language. There is still lots of vocabulary I do not know”. The female interviewee said, “Furthermore, insufficient vocabulary can be a reading difficulty for me as well”.

In contrast, not many respondents thought that ‘insufficient prior knowledge’ could be reading difficulties or influenced their understanding when reading a challenging passage. Based on the interviews' findings, the female student answered: “Yes, absolutely, I usually use my prior background knowledge to connect with the topic or some sentences which I am not very confirmed, but due to my insufficient previous knowledge, it sometimes affects my reading understanding” (Interviewee 1).

However, the male interviewee did not mention prior knowledge at all. In terms of ‘English exposure’, very few students considered a lack of ‘English exposure’ that could be their reading difficulties when reading a complex text independently. According to the interviews' findings, the 2 participants did not think they lack ‘English exposure.’ The female respondent argued in the interview:

“Uh, I think English is a foreign language for me because I am an international student. The grammar pattern is completely different, so reading in English is definitely new and hard, especially reading a challenging text. But since I am a student in Glasgow and I have many chances to use English which can help me learning English fast and help me make progress on my poor reading”.

To conclude, insufficient vocabulary was the most severe difficulty for most participants, whilst very few students considered that ‘prior knowledge’ was their reading obstacle when they read a challenging text by themselves.

Discussion. In the present study, EFL students in Glasgow preferred using cognitive strategies of ‘translation’ and ‘inferencing’ that are much more than other strategies use in general. Compared with ‘translation’ and ‘inferencing’, the participants do not consider ‘note-taking’ as their reading strategies very frequently. The result of the majority of EFL students’ perspectives of reading strategies often/always employ ‘inferencing’ which related to ‘predicting’ or ‘guessing’ from the context that is similar to the previous studies of Sarcoban (2002) Yiğiter and Gürses (2004) which were conducted in Ataturk University in Turkey. Besides, very few participants think that ‘note-taking’ is their reading strategy when they read a challenging text on their own in this own research, the result fits with previous studies which investigated Iranian EFL students who got a relatively low mean of ‘taking notes’ by Zare (Zare, 2013).

In terms of metacognitive reading strategies, most respondents prefer to use rereading very frequently in a college of Glasgow, which fit the previous results from many other studies at Mysore University and Nanyang Technological University (Cromley, 2002; Şen, 2009; Jun Zhang, 2001). More specific, interviewee 1 responded that rereading is one of her reading strategies:

“Um, if I find the text or the content is difficult, I reread it, and then read the difficult sentences 3 or 4 times and then if feel like I understand it, I move on if I feel like I do not understand that, I read it again”.

Moreover, the perception of the ‘planning’ strategy is not used very often or is used rarely. There is no noticeable trend of the use of the ‘planning’ strategy when they read a challenging text on their own based on the questionnaires, which cannot compare with previous studies from Saricoban (2002) so that cannot witness the importance of EFL students’ perspectives about the ‘planning’ strategy, it might be explained by the fact that the respondents from the questionnaires did not understand what the ‘plan’ exactly mean of the Q11 while Q12 are asked a similar question about ‘functional planning’, which result in adverse responses of the two questions. However, the outcome from the semi-structured interviews is quite identical to Saricoban (2002) study. Both of the male and female interviewees have a plan and a goal before and while reading. To be more precise, the female interviewee answered: “My goal is to get the answer to the question while reading, especially in IELTS text. I probably have a plan about what strategy I should use according to different types of questions”. Interviewee 2 stated:

“The main goal for me is to find the answers in such a challenging text if I read an IELTS text. If I read a challenging text for pleasure, my goal is to understand it, or even I do not have a goal”.

However, there is a surprising finding of the perceptions of using the ‘self-evaluation’ strategy in a college that runs foundation and preparation courses for Master’s degree students. Based on the results from questionnaires, many EFL students think that they sometimes employ the strategy of ‘self-evaluation, which does not fit previous studies (Şen, 2009; Yiğiter&Gürses, 2004). It may be because the Q14 and Q15 were asked about checking the language while reading rather than the content of the text. It can be assumed that EFL students may focus on content first to understand the passage, especially during an IELTS exam.

Additionally, the finding from the interviews shows that both of the respondents consider checking the content of a reading passage as their priority than checking the language while reading a challenging text on their own in a college of Glasgow, which is similar to the studies of Şen (2009) and Yiğiter&Gürses (2004). Thus, it can also be hypothesised that the EFL students’ perceptions of the reading strategy use relate to the different purposes of reading. The two interviewees argued, “Um, again, it depends on different situation. If I am free, I do not have exams or lots of courses, I will do that if I do not have enough time like during an exam, I will not do that”. Interviewee 2, too, believes: “Definitely yes. Nevertheless, firstly I prefer to check the content if I understand. After reading, I like to write down some new words in my notebook to try to learn and remember the new knowledge from reading”.

Most EFL students use the ‘self-talk’ strategy most frequently when they read a challenging text on their own in that college of Glasgow, and they usually show their emotion when they read a complex text on their own. Self-talk can help them to reduce reading anxiety. Simultaneously, reading, which is similar to Fotovatian and Shokrpour (2007) study at Iranian University.

Besides, the research has found another finding that they use ‘self-talk due to the reason of reading anxiety’, the English level for EFL participants in Glasgow think that English for them is high-brow, making them feel worried and tense while reading a challenging text on their own. For instance, the female interviewee said: “I always talk to myself to calm down and make me decompress; it makes me more focused on the challenging text”. She said: “I feel like I do not want to read it, and feel stressed because the English standard is a little bit high, I feel it is difficult for me, but I have to read it, I feel like it is pressure”.

However, in this research, EFL students in a Glasgow college were found that they least frequently use the socio-affective reading strategy for reading a challenging text on their own compared with strategies of cognitive and metacognitive strategies. To be more detailed, the perceptions of the use of ‘cooperation’ such as explaining the text to self or others, work with peers are the most frequently used category of reading strategies when they read passages in classes in Iranian University based on previous studies by Fotovatian and Shokrpour (2007) and Choi (2003).

The majority of EFL participants in a college of Glasgow reported that they encountered several reading difficulties when they read a challenging text on their own because they perceived that they had experienced reading difficulties while reading a difficult text on their own, which resulted from several reasons such as reading anxiety, insufficient vocabulary. One of the apparent findings of reading difficulties for the participants is inadequate vocabulary, which seems to be supported by Rucklidge and Tannock (2002), Hargis (1999) and Mourtaga (2006), who showed that good readers could recognise a wide range of complex vocabulary.

Another expected finding of reading difficulties for EFL students is reading anxiety (fear, pressure, tension), as shown in participants’ responses from the questionnaires and interviews in this study, consistent with previous studies (Javanbakht & Hadian, 2014). All the 17 participants from questionnaires and interviews thought that they all have reading anxiety, particularly facing a challenging reading passage on their own. Similarly, Language difference is another reading difficulty that tends to be supported by Nuttal (1996). No participant reported that language difference is not their reading problem.

Conclusion. The findings show that EFL students most frequently used ‘cognitive reading strategies’ and ‘metacognitive reading strategies’ compared with socio-affective reading strategies when they read a challenging text on their own in general. More detailed, the findings of the research questions indicate the following: First of all, the majority of respondents thought the most frequent strategies they use were ‘translation’ and ‘inferencing’ in terms of ‘cognitive strategies’ when they read a challenging text on their own in the college of Glasgow, and inferencing strategies such as guessing and predicting are supported by Sarcoban (2002) and Ajideh (2003).

Further, based on EFL students’ perceptions of the ‘metacognitive strategy’, many respondents preferred employing the ‘rereading strategy’ than others, which is similar to the previous study of Jun Zhang (2001). However, it does not mean these results tend to correspond with lots of previous studies implemented in other countries. Lastly, although no participants like to use the ‘socio-affective reading strategy frequently, many respondents preferred using ‘self-talk’ to decrease their reading anxiety.

In terms of answering the second research question, EFL students perceived that they had faced reading difficulties while reading a challenging text on their own, which primarily resulted from insufficient vocabulary, which instituted many respondents in this study. Slow reading speed is regarded as another severe difficulty by the perceptions of EFL students in a college runs for foundation and preparation Master’s degree students in Glasgow in this present research, which is consistent with Nuttal (1996) study does not seem to fit other previous studies. Further studies should be focused on more studies in this field of reading speed.

Limitations. This study might have some implications for further practice. Firstly, there could be a relationship between gender and the use of reading strategies when EFL students read a challenging text on their own; thus, it is necessary to investigate the strategy by sex to ensure the difference of reading strategies between male and female, so that the EFL learners can be aware of what reading strategies they use and what reading strategies are appropriate for men and women to employ when they read a challenging text on their own. Secondly, a problematic text includes IELTS text for EFL students and comprises novels, newspapers, etc. Reading different types of reading passage has various purposes for EFL learners. Therefore, EFL learners need to make sure their reading purposes when they read a challenging text independently. Thirdly, the teachers in some education institutions run for foundation and preparation for Master’s degree students need to recognise the reading difficulties and problems of EFL students to help them solve and overcome the challenges with applying proper strategies in class once they read a challenging text on their own for those students who are preparing a study in English in universities.

Список литературы