Higher education studies and pregnancy: Challenges and balances

Abstract

Introduction. Pregnancy brings about physical and psychological changes (Naim, Bhutto, 2000) such as weight gain, pain, anxiety, depression, fatigue etc. that affect daily routine. During the early weeks of pregnancy, women may feel tired with low energy levels. Some women experience heightened emotions whereas some others feel more anxious or depressed during this period. Many researchers have highlighted women’s dual identity and role as mothers and students. For example, women have traditionally been conceptualized as the careers in the family, influencing their identity construction (Alsop et al. 2008). Further, student mothers’ experience in both structural environment and socio-cultural constructs reflects complex identity inside and outside the university as they are performing as both mothers and students and rely on economic and emotional support from parents and spouses (Lynch, 2008). Marriage does not affect a woman’s performance as a student, but pregnant students have different experiences and problems in educational settings (Dempsey, Ravacon, 1971), resulting in apossible delay in the achievement of educational goals (Mason, Goulden, 2013).

Globally, the number of women enrolled in higher education institutions has been increasing. 29% of women become pregnant during their higher education studies, a figure which is likely to increase (Pugh, 2010). Pregnancy changes the current and future lives of women and can have a negative effect on education. Compared with men, 59% of married women with children leave academia and take on more household responsibilities (Mason, Younger, 2014).Previous research has employed McClusky’s theory of margin for examining issues related to students' pregnancy and their studies (e.g., Evans, Grant; 2008; Grenier, Burk, 2008; Maher et al. 2004; Merriam, Bierama, 2014; Stoddart, et al., 2013; Quinn, et al. 2019). In line with these previous studies, we also employ the McClusky's theory of margin to look deeper into the experiences of pregnant graduate students’ loads that hinder their higher education studies, and the powers to compete with all circumstances successfully. First, we present the main perspectives of the theory of margin.

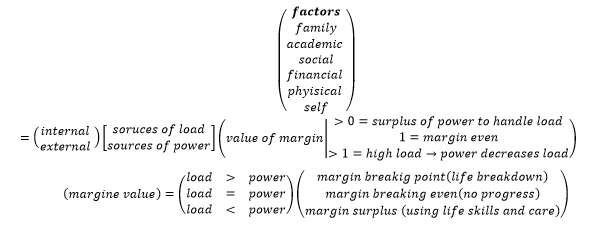

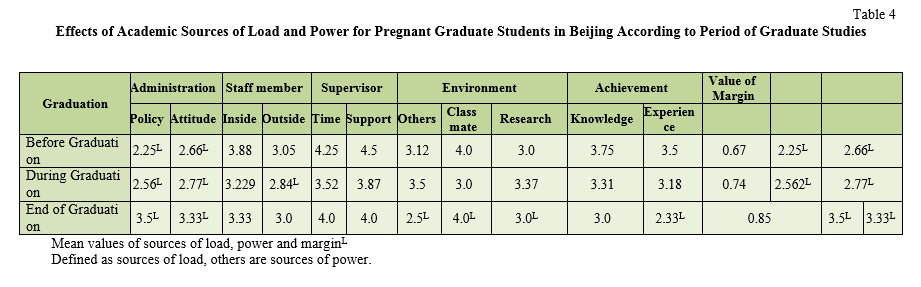

Theoretical Perspectives: McClusky's theory of margin. McClusky’s (1963) theory of margin describes the impact of increasing demands and pressures on adults’ lives over time. McClusky’s theory (1974) of power-load-margin the orizes about the load an individual carries and the power to carry that load. Margin (M) is the relationship between the load (L) and the power (P) and is defined as the ratio of load as the numerator and power as the denominator (M=L/P). Load is the demands of living and power is the personal resources or environmental supports available to cope with the load. The value of the margin ranges from above 0 (zero is an ideal case and does not exist in nature) to 1 or greater than 1. A margin value greater than 1 is an alarming condition, as it shows a high load; this demands substantial power to overcome the load. A margin value less than 1 means that there is a surplus of power available to handle the load.

McClusky (1963) further clarifies the load and power ratio by dividing load in two interacting elements: internal load and external load. External load factors are normal life tasks, such as family commitments, careers, physical demands and community. Internal load factors are life expectations, desires, aspirations and future goals. Further, Stevenson (1982) defined load as tangible or intangible objects, thoughts, sentiments, biological discrepancy or any usual task, which require energy when it is mentally entertained or physically put in place by individuals. However, according to Heimstra (1993), Load consists on tasks engross in the usual requirements of living. It has a significant value when combined with power to achieve educational goals. Power is the physical and mental abilities for both internal and external resources. External power requires support from family, social abilities and economic stability. Internal power requires self-motivation skills and experiences that contribute to successful performance, such as personality, resilience and coping skills (Main, 1979; Walker, 1997; Weiman, 1984). McClusky’s theory of margin is rooted with the complications, unique features and possibilities within the experiences of adult’s life (Main, 1979). For success, an adult needs both self–preservation and self-improvement. Adulthood is continuously changing with time and needs energy and power to keep balance between ‘loads of life’ (McClusky, 1963).

McClusky’s theory (1974), also called as power-load-margin theory, involves the load (L) which individual bears in performing multiple tasks and the power (P) to give strength to carry load. Margin is determined by ratio of load to power ((M=L/P) with a ratio at 1.00 representing an equal balance of power and load (McClusky, 1963) while ratio of .50 to .80 provides substantial margin to meet the challenges of life (Main, 1979; McClusky, 1963). The surplus of power in relation to load, the margin is available to achieve goals. Margin is associated with excess of power that adults possess (Lagana, 2007) while Merriam, Caffarella and Baumgartner (2007) restated Margin as ratio of load to power in one’s life; more power means a greater margin to participate in learning (p. 93). According to Main (1979), a person with margin is allowed to “invest in life extension projects and experiences including learning experiences” (p. 23). Moreover, the quantity and degree of margin is crucial in people’s lives. However, an individual lacking margin in life has then few alternatives with no power to exploit them (McClusky, 1963).

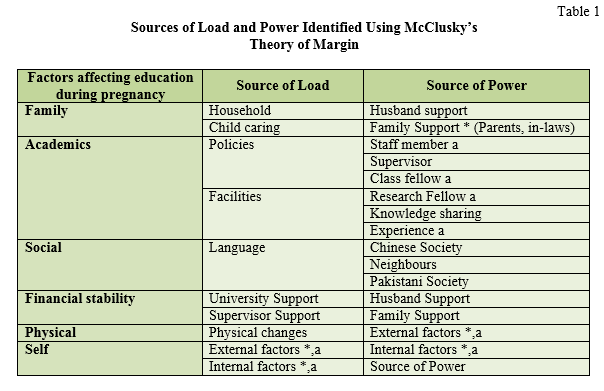

Previous research has employed the theory of margin for examining different issues/topics. For example, Grenier and Burke (2008) used McClusky’s theory of margin to explain the sources of load and power using an auto-ethnography approach. They collected data from pregnancy to childbirth from graduate students. The students’ sources of power were information and support (department, friends, family members and employers) and their loads were physical factors (lack of sleep, stress and pressure), family, academic- and job-related factors and age. Also, Maher et al. (2004) investigated how financial instability, marital factors, family, health and academic-related issues hindered women studying for their doctoral degrees. The findings revealed how some women who completed their doctoral degrees on time, had full support from their family along with their supervisors and were aware of whom to turn for support within the academic system. Further, Evans and Grant (2008) reported on the experiences of parental students. These experiences identify physical changes, household responsibilities, childcare responsibilities and academic factors as loads while internal strength, colleagues, financial support and academic factors as power. The factors experienced as loads and power vary from person to person. Additionally, the theory of margin is employed to explore both external and internal barriers faced by non-traditional students to the path of college along with their driving force or extra margin needed to traverse and overcome struggles (Stoddart, et al., 2013). It was also utilized as a philosophy of motivation for learning and how life experiences, body and spirit, motivation, cognition and culture bear on the adult learning context (Merriam, Bierama, 2014; Finally, Quinn, et al., 2019) postulated the theory of margin to overview the experiences of first generation students enrolled in a Student Support Service program by identified life factors that influence one’s level of load (demand) and power (resources) which is the key to understanding one’s margin in life. In line with these previous studies, we also employ the McClusky's theory of margin to look deeper into the experiences of pregnant graduate students’ loads that hinder their higher education studies and powers to compete with all circumstances successfully. Therefore, we categorized power and load in terms of family, social, financial, academic, physical and self-relatedfactorsshown in Table 1 below. Some factors are simultaneously sources of load and power depending on circumstances (such as time during the graduate study period, child-rearing, household responsibilities and financial stability) and vary from one person to another (as explained in the analysis section).

Note1: *Identified in previous research as a source of both load and power. However, in this study, these were solely sources of power.

Note 2: a These factors change according to the graduate study period, and are perceived as loads at certain times.

By becoming a mother, a woman enters into a new stage of her adult life that involves what Tennant and Pogson (1995) describe as “an adaptation to the changed expectations and circumstances associated with different life phases” (p. 116). Theories of individual life events cite the birth of a child as a major event in an adult’s life. In addition, theories of life transitions point out that there is a normal progression of perplexity (e.g. Merriam, Caffarella, 1999) associated with these major life events. Therefore, becoming a mother has a substantial impact on the “margin” needed for a woman to manage the many other aspects in her life that contribute to load. Following is a brief presentation of the study design and questions.

The present study. The present study followed a non-experimental design. It focuses on how female pregnant students perceive their pregnancy and the challenges facing them during their studies (i.e. the first author experienced pregnancy during her doctoral studies in Beijing). Further, the paper reports upon whether pregnancy is a source of motivation or hindrance, leading to either completing or suspending their studies. With the focus on pregnant Pakistani graduate students pursuing their higher education in Beijing, the paper also reports on how these women balance between their roles as students and mothers-to-be, how they prepare themselves for becoming mothers and how they (for those who have given birth)perform as mothers. Giventhis, the paperanswersthese research questions:

- How do pregnant graduate students manage their academic loads?

- What are the loads of a pregnant graduate student?

- What sources of power do pregnant graduate students have to overcome their loads?

Demographics. Out of 31 respondents, 29 participants (mean age of all the participants is 29.28 years) studying in different universities in Beijing returned the questionnaires. Eight participants (average age 33.5 years) already had children as they started their graduate studies. The participants with pregnancy before, during or at the end of their graduate studies in China had an average age of 27.54 years. Twenty-six participants are currently graduate students in different universities in Beijing, China, and three participants have already completed their studies. Nine participants completed their studies in 2017, ten participants in 2018 and seven in the academic year 2019-2020. Although age is an important factor that affects the experiences of pregnant graduate students, we did not examine age in this study.

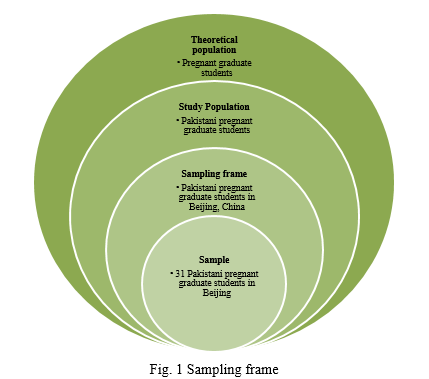

Sampling frame and procedures. This study employed a quantitative approach, mainly a survey research design. We used the snowball sampling technique known as ‘chain-referral method’ or ‘auxiliary method’ (Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2018) that also relies on social networking and interpersonal relations (Noy, 2008) for collecting data. The snowball sampling technique minimizes asymmetrical power relations between respondents and researchers, enabling it to be a valid sampling frame (Cohen, Manion, Morrison, 2018). Fig. 1 below shows the sampling frame of this study.

For data collection procedures, the authors used a structured questionnaire (see Appendix A) with two sections: the first section contained 14 multiple choice and open-ended questions-collecting background information, and the second section contained 41 scaling questions (i.e. Likert scale).All the questions were based on the theory of margin and measured sources of load and power (Table 1). The questionnaire measured graduate students’ experiences of internal and external financial, social, family, academic, physical and self-related factors during pregnancy. The physical changes that occur during pregnancy can result in self-imposed pressure that is experienced as load); however, the self can be experienced simultaneously as a source of both load and power depending upon other factors (Grenier, Burke, 2008). Similarly, Evan et al. (2007) identified the self as a load at the beginning of her studies, as it creates uncertainty, internal conflicts and doubts about one’s ability (p. 47); however, self-motivation during pregnancy facilitated the early or timely achievement of educational goals (p. 132). The data of the present study was collected online using this website: http://www.surveymoneky.com. Since the snowball sampling was used to locate the relevant participants for this study; having collected their information, they were sent the survey one by one according to recommendations from previous participants. The consent form proceeded sending the survey. However, two out of the 31 participants did not respond to the survey-ending up with 29 respondents.

Measures. Higher education studies and pregnancy are divergent trajectories and women must use all their resources to balance between these two worlds of academia and family. McClusky’s theory of margin describes how the learner must balance between load and power or resources. This frame of reference can be applied to the experiences of pregnant graduate students and their struggle to manage the relationship between load and power. We used a questionnaire to measure the sources of load and power based on McClusky’s theory of margin. A 5-point Likert response scale was used: strongly agree (1), agree (2), undecided/neutral (3), disagree (4) and strongly disagree (5). The questionnaire focuses on addressing the research questions stated earlier.

While previous research (discussed above) identified both internal and external loads, we categorized loads into the following subgroups: family, academic, social, financial, physical, and personal; we assumed that these subgroups described all possible internal and external loads for pregnant graduate students. The value of the margin ranges from above 0 (>0) to 1 or greater than 1 (≥1). The value of margin greater than 1 shows high load on pregnant graduate students (>1=high load); this demands substantial power to overcome the load. Value of margin less than 1 means that there is surplus of power available to handle the load (detailed criteria are summarised in two formula in the introduction of the section of results). We constructed the questionnaire based on these internal and external factors as mentioned above. In Likert scale, numeric value of power or load is reversed to have an equal weight. Then, we divided the load with power to calculate the value of margin.

Before sending the questionnaire to all participants, three participants completed the questionnaire to check its validity. Based on their responses, irrelevant questions were removed, and the questionnaire was revised. An analysis of variance test was used to check the reliability of the questionnaire using IBM SPSS’24 (2016). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.749 for the 41 items (29 participants); F = 6.386, p< 0.05.

We present the study results within these five themes: family, academic, social, financial, and physical factors. The values of load, power and margin are calculated using the following criteria. In order to measure the divergence between higher education studies and pregnancy, it was assumed that women need to use all their resources to balance between these two worlds of academic and family. Given this, we used the following value to calculate the experience of pregnancy of Pakistani graduate students in Beijing and their struggle to manage the relationship between load and power.

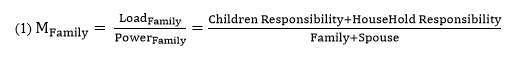

Results. Family factors. The family plays an important role in most individual’s lives. It is also more important for a pregnant graduate student to complete her education. Previous research suggests that childcare and household are sources of load, whereas support from family (especially the spouse) is perceived as a source of power that can help students complete their studies (e.g. Evan et al., 2007; Cotterill et al., 2007). Parents and in-laws were both considered as sources of power and load in relation to the fulfilment of educational goals (Evan et al. 2007; Ellis, 2014; Galmarini, 2008). If household and childcare are sources of load, then what do students perceive as sources of power to help them complete their studies? According to McClusky’s theory of margin, the effect of the family for pregnant Pakistani graduate students is as follows:

The mean value for family support was 4.05 and for spousal motivation and help was 4.48, and the overall mean of power from the family was 4.26. The perceived load for childcare or motherhood was 1.66 and for household responsibility was 1.57. The load for the family factor was obtained by reverse scoring of the responses on the 5-point Likert scale, producing a mean load of 1.615. According to the above relationships, the value of the margin for pregnant graduate students for the family factor is 0.379 thatis less than 1. This indicates that Powerfamily is greater than Loadfamily which is important for pregnant students to achieve their academic goals.

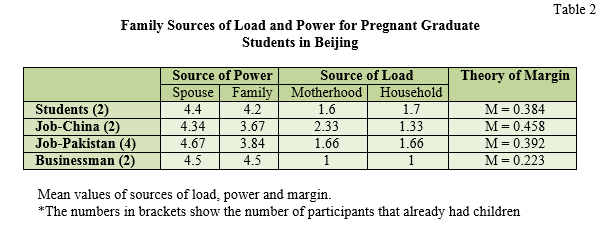

We also analysed the role of spouse as power. In our sample, 12 spouses were students, 13 were employed (five in China and nine in Pakistan) and four were running their own businesses. Table 2 shows mean scores for spousal sources of power and load and their margins using a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 2 shows the load, power and margin related to the factor of family. Spouses were a source of power that helped pregnant women to complete their higher education studies in China. It shows that husbands who work in Pakistan play a more supportive role, whereas the family plays a less supportive function. Spouses who are students and businessmen provide positive roles for pregnant women and motivate them to complete their studies. The value of margin is less than 1 − indicating a surplus of power yet requiring handling this surplus skilfully.

Students with husbands working in China had a larger mean load for motherhood than other students. Students whose husbands were businessmen showed low mean loads for motherhood and household responsibilities. The value of margin for the family variables indicates that husband who is a businessman becomes a high source of power; however, a husband with job in China is perceived as a low source of power.

We further classify participants in two categories; one who already had children and become pregnant for the second or third time (numbers in brackets in the first column of Table 2) and second who become pregnant for the first time while conducting their graduate studies in China whilst their spouses were students, businessman, or having jobs in China or working in Pakistan. The statistical analysis showed that the margins for motherhood and becoming pregnant for students whose spouses were students, worked in China, worked in Pakistan and were businessmen were 0.4, 0.25, 0.33 and 0.25, respectively. Students who were already mothers showed value of margin less than 0.5, which indicates high power value. This is because they understood the nature of being a mother, a wife and a daughter-in-law better than newly married students or those who were pregnant for the first time. The margins for students who became pregnant for the first time whose spouses were students, worked in China, worked in Pakistan or were businessmen have the value of margin 0.38, 0.56, 0.45 and 0.2 respectively. The analysis indicated that pregnant students whose husbands worked in China received less support from their family and felt great pressure to becoming a mother.

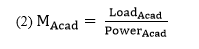

Academic factors. Academic factors such as administration, school/department, teachers, supervisor, class fellows/friends, research scholars and finance are sources of both load (Galmarini, 2008; Rab, 2010; William, 2007) and power (Ellis, 2014; Galmarini, 2008). We categorized academic factors as shown in Table 3 and analysed the questionnaire data in terms of the distribution of sources of load and power. (Financial resources affect both academic and family relationships and we discuss these in the financial factor section below). For academic achievement, both internal and external demands on the self are important in relation to the rapid physical changes experienced by pregnant women, but we discuss these factors in the next section. In this section, we focus on the role of the academic administration and its policies regarding pregnant women, staff members and their attitudes inside and outside the lecture room and the role of the research advisor and university environment (including cooperation of Chinese friends, class fellows and research students). The following relationship shows the margin (for academic factors [MAcad]) for pregnant Pakistani graduate students in China:

Table 3 shows the results of the academic factors of administration, teaching staff members, research supervisor, university environment and academic achievement. The numerical values indicate the application of the theory of margin to academic factors in terms of load and power. The margin for academic factors was 0.732; the mean value of academic sources of load was 2.475 and it was 3.382for academic sources of power. The perceived power was greater than the load, but there is still much work to do to reduce the load for pregnant graduate students.

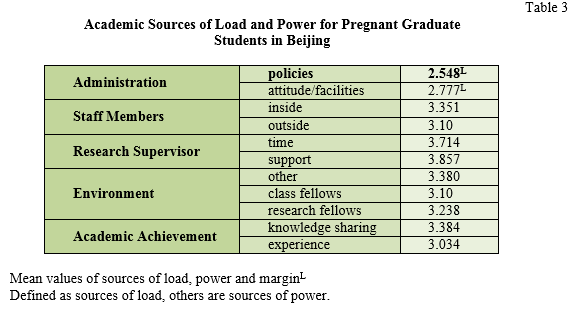

The margin for academic factors mainly depends on the study period when the assessment was conducted, as shown in Table 3. 19 participants became pregnant during their graduate studies and five families already had children, two students became pregnant at the end of their studies, eight participants became pregnant before their studies and five out of eight participants already had children. Table 4 shows the students’ academic journey according to the theory of margin and based on 5-point Likert scale ratings. First, the individual responses are quite different from the combined responses. Individual response is the assessment for before, during and at the end of the study while combined responses show the assessment throughout the period of study. At the beginning of their graduate studies, pregnant students experience the adverse effect of administrative policies and facilities and this

factor becomes worse toward the end of their studies.

Second, the analysis of the combined

responses did not indicate an adverse effect of aspects of the university environment, such as attitudes of class fellows and research students. The adverse effect of these factors might be more apparent at the end of the study period, because all students experience the same stress to complete their studies. Therefore, a source of power may convert to a source of load for pregnant graduate students nearing the end of their studies.

The academic supervisor has a positive role throughout the study period (i.e., a source of power).It is very important for pregnant students to complete their higher education studies despite adverse university policies.

The margins shown in Table 4 indicate that the effect of the loads increased throughout the study period. Pregnant students need more support to overcome this stress. Such support can be provided by the university administration by formulating policies suitable for pregnant students and providing them with an appropriate and friendly environment.

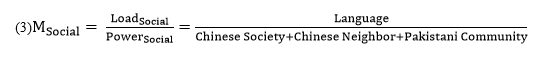

Social factors. Figure 1 shows the social values related to tradition, culture, religion and language. Do social values affect female education? The factors more directly related to participants of this study were language, Chinese society, its customs and traditions, and the role of the Pakistani community in China. We did not include the university environment in social factors (presented in the previous section). Therefore, the margin for social factors was:

These relationships indicate that the role of Chinese neighbours was only applicable to living off-campus. Most universities in Beijing do not accommodate students who are parents. These students must stay off-campus and often live far from the university, because accommodation near the university campus is quite expensive (we discuss this factor in the next section on financial factors). The social factor of language was a source of load within and outside the campus. Language is a powerful tool among individuals to communicate and share knowledge. The Chinese and Pakistani communities were perceived as a source of power whereas communication with the Chinese society was language dependent. The identified social factors possibly affecting Pakistani graduate students are religion, culture, society (both Pakistani and Chinese), language and tradition.

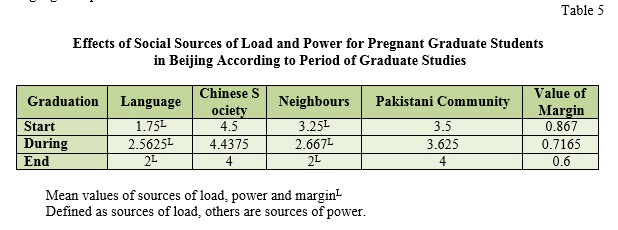

The overall margin value for social factors for pregnant Pakistani graduate students in Beijing was 0.74. The power of social factors increased throughout the graduate study period. The margins at the start of graduate studies, during studies and at the end of studies were 0.867, 0.716 and 0.6, respectively

(Table 5). The perception of language as a source of power is increased by learning and communication throughout the graduate study period. However, if the perception of language as a load increases, the value of the margin for social factors will also increase.

The analysis showed that the margin for social factors decreased with time as the power increased. The effect of the Pakistani community and the social circle increased over time, which provided more support and security to students. Language directly relates to the effects of Chinese neighbours and community. Increased language ability enhances communication with others. Therefore, the effect of language and the Chinese community were inversely proportional to each other. Another dominant factor that increased power was the Pakistani community in China. This factor counteracted the effect of language as a source of load, because it is not affected by knowledge of the Chinese language. The mean values of Pakistani community support within China at the beginning, during, and end of graduate studies were 3.5, 3.625 and 4, respectively.

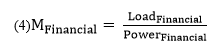

Financial factors. The financial factor is crucial for pregnant students in higher education studies. Financial expenses for maternity, accommodation and child caring build pressure on pregnant students. To overcome such financial expenses, pregnant students need jobs or a reliable source of income. The theory of margin relationships for financial factors was:

We defined financial sources of load and power as family, job, supervisor support and university financial plans and policies. The family aspect included the financial condition of the husband. Financial support and motivation from family members were also included as sources of power. Although pregnant students with some job benefit financially, they find it difficult to manage workloads, time and educational achievement. How do Chinese universities help pregnant students who are not financially stable? Do their supervisors support them with funds? Is there any policy to help pregnant graduate students to complete their higher education studies on time? The statistical analyses of the financial factors showed that the margin value for the financial factors was 0.633, and the mean values of power and load sources for the financial factors were 4.261 and 2.698, respectively.

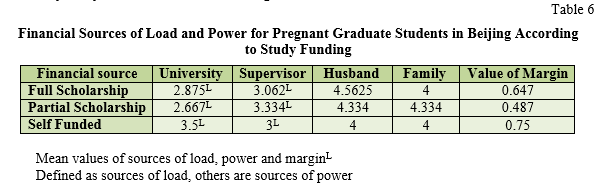

We further categorized students according to type of funding. Out of 29 participants, 20 participants had a full scholarship, 5 received a partial scholarship and 4 were self-funded. The margins for full scholarship, partial scholarship and self-funding were 0.647, 0.487 and 0.75, respectively (Table 6). The margin for partial scholarship indicated no financial load on pregnant students because their husbands were financially stable and encouraged them to complete their education. Self-funded pregnant students in higher education have less power than students with partial funding. A spousal support for partial and self-funded students was 5 and 4, respectively. Therefore, self-funded pregnant students experience more stress and pressure from their family to complete their education on time, which increases the value of the margin.

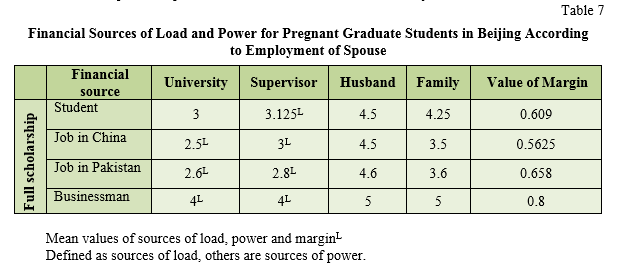

We further divided students on full scholarships into four categories according to whether their husbands were students, employees or businessmen (Table 7). Out of twenty participants on full scholarships, ten had husbands who were students, three had husbands who worked in China, six had husbands who worked in Pakistan and one had a husband who ran his own business. The mean values for the willingness of the twenty participants to enrol in higher education were, respectively, 3.75, 4.0, 4.0 and 4.0 (husbands as students, working in China, working in Pakistan and businessmen). The mean values for the husbands’ willingness for them to enrol in higher education were 4.25, 3.0, 4.2 and 5.0, respectively. The margins for pregnant students on full scholarships with spouses as students, working in China, working in Pakistan and businessmen were 0.609, 0.5625, 0.658 and 0.8, respectively. The margin increased over time because of the adverse university policies related to pregnant graduate students in Beijing. The effects of university policies on the value of the margin were 0.7, 0.625, 0.731 and 0.734, respectively. The Likert scale scoring showed that university policy directly influenced financial stability.

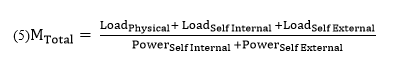

Physical factors and self-factors. The physical effects during pregnancy are experienced as sources of load with variation among women. In our study, we categorized the external factors into family, academic, social and financial factors. Further, we categorized internal factors into emotions and self-motivation. While physical changes during pregnancy are taken as load in equation 5, the analysis demonstrated the role of internal and external self-factors in overcoming the physical condition of pregnant students:

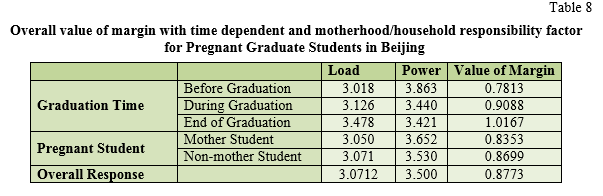

Where LoadPhysical represents the physical changes related to pregnancy, which cause anxiety, fatigue, stress and depression, LoadSelf Internal and LoadSelf External represent sources of load experienced by pregnant students that depend on external and internal factors. Examples of external factors are the role of the university administration, support from teaching staff, guidance from a research advisor, motivation from the family (especially from the husband) and, most importantly, financial stability. Internal loads are low energy levels, depression and stress related to educational achievement, morning sickness and stress. On the other hand, self-factor can also be a source of power. The overall margin for pregnant students was 0.877. The value of the margin was also time dependent. At the beginning, during and at the end of graduate studies, the margins were 0.7813, 0.9088 and 1.016, respectively. Other factors, such as whether the student was already a parent or whether they were pregnant for the first time, produced margins of 0.

The margin values suggest that pregnant Pakistani graduate students experienced more power than load. However, a close examination of time-related changes in the value of the margin shows that load increases with time at the end of the studies. Therefore, the time during the studies influences the distribution of load for pregnant graduate students. Women’s experience in handling pressure or physical changes was also an important factor. Women who already had children knew how to use the system to work for them compared with those who did not have children during their studies in Beijing. Finance was another important factor that affected the balance of work, family and academic life.835 and 0.869, respectively, as shown in Table 8.

Discussion and conclusion. The study results highlight the experiences of the Pakistani female pregnant graduate students while conducting their higher educationstudies in Beijing. We specifically examined the family, social, academic, financial, physical and self factors affecting Pakistani female pregnant graduate students. The main assumption was the ability of the students to balance between power and load to achieve a balanced margin; the ability of the students to balance between their pregnancy and academic lives. The calculated values of power were greater than those of load for the five factors—resulting into margin values of less than 1 for all these factors (Family=0.379, academic=0.732, social=0.74, financial=0.633, physical and self=0.877.) Further, time showed as an affecting factor − changing the value of margin accordingly (i.e. starting period of study, in the middle of the study period and towards graduation). Given this, we discuss the results of the present study in five dimensions.

First, concerning the family factors that possibly affect Pakistani female pregnant graduate students, our results showed that the roles of in-laws and parents were dominant than those of husbands but both are used as sources of power. This contradicts with Gr enter and Burke (2008) who found that the in-law role was a source of both load and power. However, our results support previous research that family support helps women in higher education to achieve balance in their lives (e.g., Di Georgio-Lutz, 2002; Williams, 2007). Sometimes, the effort of balancing between work and family can become a source of stress. Before marriage, the positive attitudes of parents and brothers encourage women to enter higher education while after marriage the support of husband becomes more important for woman to continue higher education studies. Family support to women’s education in Pakistan is influential (Rana, 2007; Saxena, 2014) although husbands are more influential on the decisions of their wives (Rab, 2010). Those who complete their higher education studies had their husband’s support in childcare, in household responsibilities and in responsibilities outside the home.

Second, the results concerning the academic factors indicate that sources of load are administrative policies, administrative attitudes and teacher support outside of the classroom − consistent with (Evan et al. 2007; DiGeorgio-Lutz, 2002). Moreover, sources of power are the supervisor’s support, the university environment and aspects of academic achievement, such as knowledge sharing and previous experience (Ellis, 2014; Evan et al. 2007). Academic support is important to ensure that parental students achieve their goals (Zachry, 2005). Such support for young women in academia helps achieve their educational goals and builds a successful future for themselves and their children. Besides, administrative policies for pregnant graduate students should be flexible. Policies for pregnant women in the workplace can demonstrate gender disparity and force pregnant women to leave their jobs (Fox, Quinn, 2015). Further, the supervisor was a source of power for students to complete their studies on time (Grenier, Burke, 2008; Mehar et al. 2004). In “Mama and PhD”, the authors shared successful experience sin achieving academic tasks efficiently because of supervisors’ positive feedback (Evans, Grant, 2008).This means that poor advice from supervisors and faculty members may lead to delays in completion of studies.

Third, with reference to social factors, our results mainly report that language has an influence on pregnant postgraduate students’ studies. The language is important as it might lead to poor communication that becomes a barrier in continuing higher education. Previous research reported that region but not religion poses challenges for higher education (Malik. Li, 2014), region is reported be more influential than religion in Pakistan (Shafi, 2011). According to Mahbub ul Haq Human Development Centre (2000), Muslim women need inspiration and encouragement from their family and society toward fur the ring their education.

Fourth, our results show that financial factors related to maternity, accommodation and child caring are important for the success in higher education studies. The results also show that the presence of reliable income source is crucial. Such results support previous research concerning educational goals achievement (e.g., Ellis, 2014; Galmarini, 2008; Lynch, 2008). Further, our results pointed out the need of the university administration to provide in-campus housing for pregnant students for lessening some pressures. This goes in vein with the assumption that it is the responsibility of the university administration to provide female students with accommodation during pregnancy (McNee, 2013).Providing educational and financial resources during early parenthood (Duncan, 2011) through, for example, governmental agencies (for educational institutions) would help retain such students, particularly in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (Maso, Younger, 2014).

Fifth, our results show that the physical condition is one important factor in the pregnant students’ successful continuity of higher education studies. If such factor is not well considered, it may delay pregnant students’ educational achievements (Mehar et al. 2004) or may lower the self-motivation to complete academic goals early (Galmarini, 2008; Rab, 2010). Grenier and Burke (2008) differentiated between internal and external aspects of the self, which may be experienced simultaneously as sources of power and load under different circumstances.

In conclusion, we highlight that our study has both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, our study contributes to the existing literature using the theory of margin with special focus on a psychological perspective on higher education studies, namely, pregnant graduate students’ stress and pressure caused by several factors varying among family, academic, social, financial, physical and self-factors. In practice, pregnant graduate students require more attention and positive support from their family and spouses, the academic environment and society in order to overcome challenges and complete their higher education studies. In particular, pregnant students need more academic support (e.g., support from the university administration and the university environment). This requires a re-evaluation of the university administrative policies regarding pregnant graduate students with a focus on lessening stress and pressure facing pregnant students. Students with such overall support can balance between their higher education studies and pregnancy. Finally, because of the difficulty in recruiting more participants during the period of conducting this study, the results are not generalizable but can form a basic step and contribution for future large-scale studies.

Reference lists

30 (1), 19-33.